The Run Loop: Part 1

The following post cuts to the very core, pun intended, of SproutCore: the Run Loop.

What is a Run Loop?

In order to ensure that we’re all talking about the same thing, here’s the definition from Wikipedia:

In computer science, the event loop, message dispatcher, message loop, message pump, or run loop is a programming construct that waits for and dispatches events or messages in a program. It works by polling some internal or external "event provider", which generally blocks until an event has arrived, and then calls the relevant event handler ("dispatches the event").

That’s a bit of a high-level definition, but I’ll try to expose the “bare metal” of SproutCore’s Run Loop enough so that it makes sense not only theoretically, but practically too.

What is the Run Loop?

In the context of SproutCore, the Run Loop is a function that coordinates code, key-value notifications, and timers within your application. Typically, a new Run Loop will automatically be started by SproutCore in response to the browser firing certain events, but a new Run Loop can be manually started at any time by placing your code between a SC.RunLoop.begin() statement and a SC.RunLoop.end() statement.

At this point, you may be thinking, “All right, smart guy, it’s easy to make general statements like ‘firing certain events’, but what events exactly?”. All right, smart reader, heaven forbid we leave anything to ambiguity. Let us look at the events that SproutCore listens for.

What triggers a Run Loop?

If you delve into the RootResponder code, you’ll find that SproutCore registers itself to receive the following events from the browser’s document:

-

touchstart -

touchmove -

touchend -

touchcancel -

keydown -

keyup -

beforedeactivate -

mousedown -

mouseup -

click -

dblclick -

mousemove -

selectstart -

contextmenu -

focusinFor IE only -

focusoutFor IE only -

webkitAnimationStart -

webkitAnimationIteration -

webkitAnimationEnd -

transitionendFor platforms that support CSS transitions only

and the following events from the browser’s window:

-

resize -

focusFor non-IE browsers -

blurFor non-IE browsers

If you look at the code in SC.device, you’ll also find these listeners on the window:

-

online -

offline -

orientationchange

and there are also listeners for devicemotion and deviceorientation in the experimental framework’s SC.device extension. Now, if you were to follow the code further, you will find that each of these events does some amount of set up, but invariably ends up creating a new Run Loop.

When should you manually trigger a Run Loop?

So, we know that SproutCore will start a new Run Loop in response to any of the many events previously listed– and I apologize if I’ve missed any– but the point is, if we better understand when SproutCore is creating Run Loops, we should also better understand when it is not creating them.

For instance, SproutCore does not listen for copy or paste events, so if you were to add your own listener, ex. $('my-input').on('copy', function() { ... }), you must also start your own Run Loop, ex. $('my-input').on('copy', function() { SC.RunLoop.begin(); ... SC.RunLoop.end()}).

However, this is a rare case, since SproutCore’s built-in libraries do trigger Run Loops properly. For example, using SC.Request ensures that a Run Loop is triggered when the browser receives a response from the server, and using SC.Timer ensures that a Run Loop is triggered when the timer expires.

So it is actually quite likely that you will never need to manually start a Run Loop, but hopefully you now understand better when you may need to.

What does the Run Loop do?

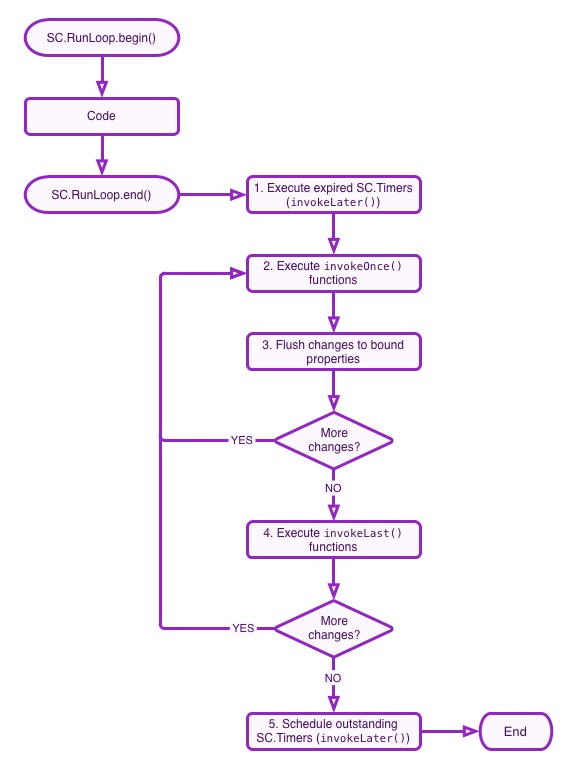

Earlier, I mentioned that the Run Loop “coordinates code, key-value notifications and timers within your application”. So, what does that mean exactly? Well, to explain it best, I’ll walk you through a flow diagram of the Run Loop.

You’ll notice the functions invokeOnce(), invokeLast() and invokeLater() in the flow diagram. These are important functions that you are most likely already using to coordinate your code execution. In order to understand exactly how they are and should be used, let’s follow very closely as the Run Loop executes.

Run Loop Walkthrough

1. Execute expired SC.Timers (invokeLater())

Any timers that have just expired will be run. This includes functions passed to invokeLater() or SC.Timers that were manually created.

2. Execute invokeOnce() functions

Your code may have added a number of functions to the invokeOnce() queue. Those functions will now be run in the order they were added, i.e. first-in-first-out.

3. Flush changes to bound properties

Now things start to get really interesting. Several observable properties may have been changed by your code using Key-Value Coding, i.e. set(), which means that these properties’ bound properties should be updated. So propagate the changes through to the bindings.

Note: properties that are observed using .observes() or addObserver(...) get updated immediately as they change, while bindings update asynchronously within the Run Loop. That is why bindings are less taxing on the application’s performance.

More changes?

At this point, steps 1., 2. and 3. may have caused new functions to be added to invokeOnce or more observable property changes. So the Run Loop will continue to repeat these steps until all the updates have propagated. When the application’s state has settled, the Run Loop will continue.

4. Execute invokeLast() functions

Now that all the changes have propagated through the app, the functions queued with invokeLast() will be run. This illustrates the common use for invokeLast(), to act upon the application when its state is guaranteed to be synchronized.

More changes?

Of course, the functions passed to invokeLast() may have again added code to invokeOnce() or changed observable properties. If so, then go back and continue to flush changes until the application state is again completely in sync.

5. Schedule outstanding SC.Timers (invokeLater())

Finally, if there are still timers outstanding, the Run Loop simply schedules a new timeout to start a new Run Loop when the timer expires.

Conclusion

Hopefully you have now learned as much as you would care to know about what the Run Loop is and how it operates, but the outstanding question is “Why?”. The answer to that question is performance and synchronization, which I will delve into in part two of this series.